Institutionalized Racism

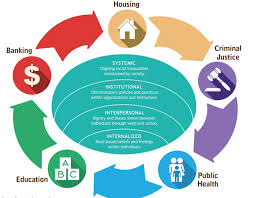

Institutional (institutionalized) racism, otherwise called systemic racism, is a type of prejudice that is inserted as a typical practice inside society or an association. It can prompt such issues as separation in criminal equity, business, lodging, medical services, political force, and training, among different issues. Institutional racism can adversely affect individuals, particularly students in the school where it is quite conspicuous. [1]

Contents

History of Institutionalized Racism

History of suppression focusing on the African-American people group across US history begins from the slavery of Black people in 1619. However, in the long run, slavery turned into a highly disputed issue. It depended on monetary reasons for white Americans, which prompted a destructive division between North and South America. With the development of both enlightened and dominant black pioneers in the twentieth century, things started to change.

After Civil Rights Movement

The progressive allure of Civil Rights Movement motivated another huge scope of development during the 1950s. Albeit the development contained numerous pioneers from assorted foundations, it has been for the most part related to Martin Luther King Jr., and furthermore esteem in peaceful opposition, as expressed by fabled Indian pioneer, Mahatma Gandhi. The development is additionally credited for the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which finished racial segregation, employment as well as electoral discrimination.

Black Power

While the Civil Rights development could change different biased laws and discernments in the US, some racism practices kept on going in American public activity, especially, in the most white-dominated police offices. During the 1960s, the Black Power development arose as police brutality against black people expanded across the US. [2]

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton initially wrote on the idea of institutionalized racism in their 1967 book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation. There, they introduced the concept of institutionalized racism by depicting an imaginary scenario. If a black family moves into a house in a white area, and they are stoned, consumed or steered out, they are victims of a plain demonstration of individual racism which most people will disapprove of. However, it’s actually the institutionalized racism that keeps black people trapped in haggard ghetto apartments, subject to the day-by-day prey of manipulative slumlords, traders, credit sharks and oppressive realtors. The general public either pretends they don't know about this, or they are unequipped for doing anything significant about this issue. [3]

Impact of Institutionalized Racism

There is no official meaning of institutional racism — or the firmly related ideas and foundation of it — albeit different definitions have been offered. All definitions clarify that racism isn't just the consequence of private biases held by individuals, but at the same time is delivered and replicated by-laws, rules, and rehearses, authorized and surprisingly executed by different degrees of government, and implanted in the financial framework just as in social and cultural norms. Facing racism, in this way, requires changing individual perspectives, yet besides changing and destroying the arrangements and establishments that undergird the U.S. racial ranking order.

As an estate of African oppression, institutional racism influences both populace and individual wellbeing in three interrelated spaces: redlining and racialized private housing, mass imprisonment and police assault, and health inequities (inconsistent clinical consideration). These models, among others, share certain cardinal highlights: hurts are verifiably grounded, include numerous establishments, and depend on the racist social image. [4]

Housing

Homeownership is intently attached to The American Dream whereby people and families seek to live in a neighbourhood with various conveniences (such as supermarkets, amusement parks, and green spaces), dependable infrastructure, and highly accredited schools. Logically, The American Dream is open to all dedicated residents. In actual, formal and informal arrangements have been efficiently carried out to confine the versatility or restrict options for nonwhite families. Lending policies, for example, redlining and ruthless loaning have since quite a while ago characterized, and solidified, the racial separation in housing accessibility and affordability, housing quality, and the geographic sharing of accessible housing in the U.S. The outcome implies that black people and other person-of-colours are bound to be three times as poor as whites, live in homes valued at 35% less than white peers. This influenced their access to substandard education, thus improving the probability of capture, arraignment, and detainment caused by polices’ racial profiling. [5]

Justice System

Police brutality against minorities is an astounding type of racial brutality that the criminal justice system perpetuates each day. As of now, there are 2.3 million individuals housed in US prisons and other criminal-equity offices. It implies that the U.S. has the biggest jail populace on the planet. While these numbers, all by themselves, maybe vexing, they become considerably seriously upsetting when we think about the racial geology of the US jail populace: ethnic minorities, especially individuals of colour, are lopsidedly addressed among the individuals who are detained.

While black people comprise 12% of the U.S. population, they comprise 33% of the jail population. Consequently, black people are significantly overrepresented in the nation's penitentiaries and correctional facilities. Michelle Alexander wrote in her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness that in Washington, D.C., 3 out of 4 youthful black individuals (and almost every one of those resides in the low economic neighbourhood) can hope to spend time in jail. On a public scale, 1 out of 3 black people ought to hope to be imprisoned during their lifetimes. [6] Alexander's research shows that 70% of black people who are released from prison, return in practically no time. It's a pattern we have seen play out as of late, which disentangles the high recidivism rates on black people and the inequality they must face in looking for after getting out of prison. [7]

Health Inequities

The term institutionalized racism highlights the most persuasive socioecological levels at which racism may influence racial and ethnic wellbeing imbalances. Isolation in schools, work environments, and medical services offices may likewise add to wellbeing incongruities. For example, Walsemann and Bell (2010) found that school isolation is identified with wellbeing behaviours (e.g., liquor use) among students. The isolation of informal communities may add to racialized designs in the spread of irresistible infections (Freeman 1978). Differences in the spread of certain sicknesses reflect existing examples of social seclusion in which black people are more socially isolated than individuals from other racial communities are. [8]

Racism is related to worse mental and physical wellbeing results and unsatisfactory patient experience in the medical services system. As proved by the COVID-19 pandemic, the race is a sociopolitical construct that keeps on disadvantaging Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other people-of-colour. [9] Emergency clinics and health facilities, which were once assigned for racial and ethnic minorities, keep on encountering huge monetary limitations and are frequently under-resourced and inappropriately staffed. These issues bring about imbalances in admittance to and nature of medical care and are significant supporters of racial and ethnic wellbeing inconsistencies. While isolation and segregation dependent on race and identity are not, at this point legal today, a few associations keep on separating dependent on protection status, which additionally excessively impacts black people. [10]

Reference

- ↑ Institutional racism. Wikipedia. Retrieved on March 23, 2021.

- ↑ TRT World Writer. (2020, May 29). How structural racism shaped Black movements in the US. TRT World. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ O'Dowd, M. F. (2020, February 25). Explainer: What is systemic racism and institutional racism?. The Conversation. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Bailey, Z. D., Feldman, J. M., & Bassett, M. T. (2021). How Structural Racism Works — Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 768–773. Retrieved on March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Blessett, B., Littleton, V. (2017). Examining the Impact of Institutional Racism in Black Residentially Segregated Communities. Ralph Bunche Journal of Public Affairs, Volume 6 Article 3, page 2. Retrieved on March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Bridges, K. M. (2020, June 11). The Many Ways Institutional Racism Kills Black People. TIME. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Thoai, L. (2011, March 30). Michelle Alexander: More Black Men in Prison Than Were Enslaved in 1850. Colorlines. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Gee, G. C., & Ford, C. L. (2011). STRUCTURAL RACISM AND HEALTH INEQUITIES. Du Bois review: social science research on race, 8(1), 115–132. Retrieved on March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Sexton, S.M., Richardson, C.R., et al. (2020, October 15). Systemic Racism and Health Disparities: A Statement from Editors of Family Medicine Journals. The Journal of Family Practice, 69(8). Retrieved on March 23, 2021.

- ↑ Institutional Racism in the Health Care System. (n.d.). Retrieved March 23, 2021.