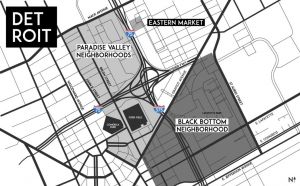

Black Bottom and Paradise Valley Neighborhood

Black Bottom was a predominantly black neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan demolished for redevelopment in the early 1960s and replaced with the Lafayette Park. It was located on Detroit's Near East Side and was bounded by Gratiot Avenue, Brush Street, Vernor Highway, and the Grand Trunk railroad tracks. Its main commercial strips were on Hastings and St. Antoine streets. An adjacent north-bordering neighborhood was known as Paradise Valley.[1]

Paradise Valley was the business district and entertainment center of a densely-populated African-American residential area in Detroit -- known as Black Bottom -- from the 1920’s through the 1950’s.[2]

The two were not, however, considered to be the same neighborhood. Historically, this area was the source of the River Savoyard, which was buried as a sewer in 1827. Its "bottom" and rich marsh soils are the sources of the name "Black Bottom."[1] Together, both Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were bounded by Brush Street to the west and the Grand Trunk railroad tracks to the east. Bisected by Gratiot Avenue, the area known as Black Bottom reached south to the Detroit River. To the north to Grand Boulevard was defined as Paradise Valley.[3]

History

Black Bottom was named by French settlers who farmed the area. It was named “Black Bottom” for its dark, fertile soil and low elevation. In the twentieth century, Black Bottom became one of the most vibrant African American districts in Detroit. In the early 1900s, many African Americans migrated north to Detroit seeking employment in the city’s growing industries. Racially discriminative housing covenants forced most of them to settle in Black Bottom, altering the connotation of the district’s name.[4] The cramped near east side neighborhood of Black Bottom was one of the very few areas blacks were allowed to reside.[2]

As thousands of blacks streamed into Black Bottom, the community swelled with vibrant cultural, educational, and social amenities. The district reached its social, cultural and political peak in 1920. Blacks owned 350 businesses in Detroit, most within Black Bottom. The community additionally boasted 17 physicians, 22 lawyers, 22 barbershops, 13 dentists, 12 cartage agencies, 11 tailors, 10 restaurants, 10 real estate dealers, 8 grocers, 6 drugstores, 5 undertakers, 4 employment agencies, and 1 candy maker (Williams). [4] The nightclubs and theaters in Paradise Valley were a primary source of income for the residents of the impoverished neighborhood. Black-owned nightclubs booked popular black artists and attracted mixed-race audiences to shows.[2]

The number of blacks moving into the district continued to increase with the promise of available industrial jobs. Increased demand for housing in Black Bottom allowed landlords to charge exorbitant rents for units in extreme disrepair. This prompted many tenants to take in boarders, further increasing crowding and the degradation of living conditions in the district.[4] Black Bottom suffered more than most areas during the Great Depression, since many of the wage earners worked in the hard-hit auto factories. During World War II, both the economic activity and the physical decay of Black Bottom rapidly increased.[1]

Despite the prosperity that emerged, most of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley remained far from glamorous, Black Bottom being the poorest section in all of Detroit, and a third of black Detroiters living crowded within Paradise Valley to the north. It was not uncommon for homes to have three, even four families inhabiting the space. The name “Paradise Valley” itself acted as an oxymoron; it represented the hopes held by Detroit immigrants and migrants, hopes not generally achieved. Overcrowding, disease, crime, and vermin ran rampant within the boundaries of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, right alongside prospering businesses, music, and fame. In addition, houses constantly suffered a state of deterioration, as they were the oldest homes in the city. This worked against the majority black populace because they were unable to afford--due to employment discrimination, particularly, income inequality, and high housing costs--repairs or beautification projects, perpetuating the discriminatory idea that lazy, dirty tenants filled these neighborhoods.[5]

The city government considered these areas slums, and because the government used highway construction projects to raze slums, they designated those remaining after the highway construction for clearance through a series of revitalization projects that permanently destroyed Black Bottom and Paradise Valley.[5]

Demolition

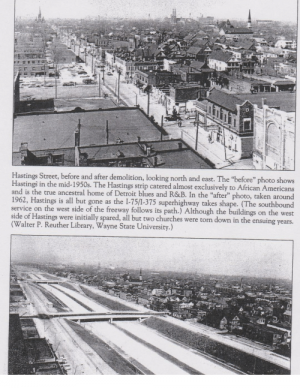

In the early 1960s, the City of Detroit conducted an Urban Renewal program to combat what it called "Urban Blight." The program razed the entire Black Bottom district and replaced it with the Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park, a mixed-income development designed by Mies van der Rohe as a model neighborhood combining residential townhouses, apartments and high-rises with commercial areas.[1] Urban renewal programs and the construction of freeways in the 1960’s abruptly halted life in Paradise Valley and the Black Bottom neighborhood. Automobile manufacturers outgrew city factories and relocated to new sites in suburban areas such as Livonia, Wayne and Dearborn. Expressways were needed to make it easier for workers to commute from Detroit to the suburban plants. Consequently, the Chrysler Freeway was built and paved over much of Paradise Valley.[2]

The Housing Act of 1949 provided cities with funding to clear neighborhoods deemed to be blighted, and Detroit was one of the first cities to take advantage of what would by 1985 amount to $13.5 billion for “slum” clearance and redevelopment projects.[6] The Chrysler Freeway blasted through Paradise Valley and Black Bottom, destroying a vibrant Black business and entertainment district that contained some of the African-American community’s most important institutions. The Lodge Expressway (M-10) cut through the increasingly Black neighborhoods around 12th Street and west of Highland Park, and the Edsel Ford Freeway (I-94) managed to cut through both the Black west side and the northern extension of Paradise Valley.[7]

Highway planners sold the demolition programs as part of an “urban renewal” campaign designed to help residents by replacing older homes and apartments with new construction. In practice, it amounted to “negro removal”: Predominantly Black and poor residents displaced by the demolition were left to find new housing without government assistance at a time when demand in the city’s segregated housing market far outstripped supply. Instead of moving into better living conditions, a majority of those displaced ended up within a mile of the new super-highways, in homes that were almost no better than the ones they had left.[7] It was replaced by a middle-class set of townhouses, and high rise apartments and condominiums units called Lafayette Park, albeit designed by world-acclaimed Mies van der Rohe. By October 1956, Pavilion Luxury Apartments broke ground. Construction of the I-375 portion of the Chrysler Freeway followed in 1959, effectively killing Hastings Street, the business thoroughfare that bridges Black Bottom and Paradise Valley.[8]

About three-quarters of Lafayette Park’s population was white, according to 1970 census figures. Because of the manner in which the land was taken and the clumsy way in which people were displaced, coupled with the lack of available housing units, the Detroit Free Press in 1974 called the effort “urban renewal’s first fiasco.”[8]

Black Bottom, which had become home to 300 Black-owned businesses by the 1930s, was completely gutted. Not a single structure still stands from the old neighborhood, which was amongst the city's densest and had once been home to Jewish, German, Italian immigrants as well as African Americans from the southern United States.[7]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 BLACK BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD. Encyclopedia of Detroit. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 PARADISE VALLEY. Encyclopedia of Detroit. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021.

- ↑ MacDonald, Cathy. "Detroit's Black Bottom and Paradise Valley Neighborhoods". Walter P. Reuther Library. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 A BRIEF HISTORY OF DETROIT’S BLACK BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD. May 18, 2012. roguehaa.com. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Sugrue, Thomas J. (2005). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. United States: Princeton University Press. pp. 23, 24, 47, 62, 196. ISBN 978-0691121864.

- ↑ Crawford, Amy. Capturing Black Bottom, a Detroit Neighborhood Lost to Urban Renewal. Feb 15, 2019. bloomberg.com. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Nithin, Vejendla. Freeways are Detroit's most enduring monuments to racism. Let's excise them.| Opinion. Jul 5, 2020. freep.com. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Coleman, Ken. Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, What Happened?. May 17, 2017. detroitisit.com. Retrieved Jan 20, 2021